Zuni Mountain Railroad CO.

1882-1941

The Zuni Mountains in western New Mexico were home to a steam logging railroad that lasted for about thirty years. The railroad was built to establish a lumber industry in the region. The logs were transported to sawmills on the railroads in the woods, and the resulting lumber and wood products were shipped to markets as far away as California, Colorado, and Missouri. However, the industry was unable to establish itself permanently due to various factors such as complex land and timber ownership, long distances logs had to be carried, and unstable markets. When all the trees were depleted, the lumber industry closed its mills, removed the railroad tracks, and moved elsewhere.

The logging railroads left their marks on the woods with clear-cut areas, remnants of roadbeds and bridges, and the remains of several towns. The Southwestern Region of the USDA - Forest Service commissioned a study to produce a history and description of the logging railroads that traversed the Zuni Mountains. The study also provides descriptions of typical artifacts and engineering features of the logging railroads where applicable, to assist those responsible for subsequent studies and surveys of the cultural resources in the Cibola National Forest.

The numerous railroad lines built within the mountains have left numerous traces of their existence. In the arid climate of the high country, sizable fragments of roadbed have survived well enough to be readily followed on the ground or detected on aerial photographs. In many locations, culverts, small bridges, and earth fills remain nearly intact. Moreover, in various locations, significant structures such as rock cuts, large fills, and cribbed log trestles remain largely unaltered since their last use. Random artifacts ranging from common track spikes to a car body part or two left following an accident can be found around these remnants of the railroad.

Recently, one co-author examined three instances of railroad construction in the company of Forest Service archaeologist David Gillio. These instances vividly demonstrate the nature of logging railroad remains to be found in the Zuni Mountains. The Pine Canyon railroad represents upland construction, with a minimal roadbed linking substantial cribbed log bridges or fills across shallow watercourses. The Valle Largo railroad was constructed heavily, with rock cuts and earth fills of substantial dimensions. The third line, the McGaffey Company mainline in Six Mile Canyon, represents a carefully engineered line laid out by the engineering staff of a mainline railroad to the specific demands of the logging industry. Each line is discussed comprehensively in the appropriate section of the report.

Part of the logging railroads' operations in the Zuni Mountains predate the creation of the National Forest. Fortunately, several key business and engineering records have survived, forming the basis of this history. The information was obtained by several individuals over a period of years as an effort of historical interest rather than a formal history. Nevertheless, the material presented here provides a reasonably comprehensive view of the business and technical history of the logging railroads.

The history of the lumbering industry in the Zuni Mountains is closely connected to the mainline railroad that runs north of the mountains. Initially constructed as the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (A&P) and now known as the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (ATSF), the A&P was the source of the land on which the pine timber grew. The land was part of a federal land grant earned when the A&P was initially constructed. The mainline was also one of the larger customers for lumber and timber, especially in the form of crossties and bridge timbers. Lastly, the mainline was an integral part of the transportation system that transported logs from woods to mill and the finished products from mill to distant markets.

Atlantic & Pacific Railroad

In the 1850s, Lt. A.W. Whipple explored the possibility of a railway north of the Zuni Mountains. The route he surveyed, known as the Thirty-Fifth Parallel route, crossed the Rio Grande near Isleta Pueblo, followed the Rio San Jose past Laguna and north of Acoma, and then crossed the lava beds near Fort Wingate. To avoid the heavily forested Zuni Mountains, the line turned northward and continued westward into Arizona.

In 1866, Congress passed an Act chartering the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, which authorized the construction of a railway from Springfield, Missouri, through Albuquerque, and along the Thirty-Fifth Parallel to the Pacific by the most practical route. To encourage the company, Congress granted land aid, including a right of way one hundred feet wide, exempt from taxation in the territories. The company could not select any mineral property, except for coal or iron. The railroad had to earn the land by actually building the line, with the right received from three inspecting federal commissioners to additional property with each twenty-five miles of road accepted as finished.

The Atlantic and Pacific's affairs were unsettled in the 1870s, but in April 1880, the Atlantic and Pacific had been reorganized as the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway (SLSF), or "Frisco," as it was commonly called. The SLSF had already earned the railroad 510,497.86 acres of land.

In 1880, the AT&SF and SLSF joined forces to build a railway from Albuquerque to California. The Atlantic and Pacific was revived under joint ownership and began building a railway west from a junction with the AT&SF at Isleta, New Mexico, during the summer of 1880. As construction was pushed across New Mexico and into Arizona during 1880 and 1881, the timber resources of the Zuni Mountains became very important. The Atlantic and Pacific depended on the Zuni Mountains' timber to provide crossties for the railway, as no other timber was available near the route of the railway in New Mexico.

J.M. Lotto won the contract to provide ties for the Atlantic and Pacific and subcontracted an order for a half-million ties, enough for 200 miles of single track, to John W. Young in late 1880. Young established a tie-cutting company at Bacon Springs near the continental divide, which later became known as Coolidge. A railroad station was built at Coolidge, which was renamed Dewey in 1898 and then to Guam in 1900.

During the 1880s, three additional lumbering enterprises operated in the mountains south of Coolidge. The first was owned by James and Gregory Page, who set up a sawmill and lumber yard at Coolidge. Later in 1889, Henry Hart and W.S. Bliss operated mills south of Coolidge. Soon afterward, Bliss joined forces with J.M. Dennis in another lumbering operation nearby.

By this time, the Atlantic and Pacific had extended its service into California and had helped open up a very active lumber industry around Flagstaff, Arizona, as well. The stage was set for the expansion of lumbering in the Zuni Mountains, which became a crucial resource for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad's growth and success.

Mitchell Bros.

1892-1893

In the late 1800s, the railroad received a valuable A&P land grant. To be useful, this land needed to be sold for cash or converted into a source of revenue. Although the arrangement was complex, with railroad sections mixed with federal or private sections, some large areas of railroad land were sold. Lumbermen bought timbered sections in Flagstaff and Williams, Arizona, while the famous Hashknife outfit, also known as the Aztec Land and Cattle Company, purchased over a million acres of grazing land between Flagstaff and Holbrook.

However, in New Mexico, only one significant sale of forest land took place. On June 30, 1890, William W. and Austin W. Mitchell from Cadillac, Michigan, purchased 314,668.37 acres of land and the timber on it. The property was mortgaged for $478,002.48 at the time. The Mitchell Brothers also purchased 2,720.44 acres of homestead and other lands in the same district. William W. Mitchell was the most active member of the Mitchell Brothers firm. He started his career in the lumber trade with his uncle and, in 1877, formed a partnership with J.W. Cobbs to purchase timberlands in the vicinity of Cadillac, Michigan. The partnership owned and operated several sawmills in connection with the timber. By 1892, the partnership was operating a mill in Cadillac with a capacity of eighty thousand board feet a day. They also had a supply of pine and hardwood timber that could last for about five years. William W. Mitchell was also associated with his brother, Austin W. Mitchell, in other enterprises, such as the Cadillac Handle Factory.

The Mitchell brothers were experienced lumbermen who knew how to run sawmills and narrow-gauge railroads used to transport logs to the mills. Records indicate that the brothers had operated several narrow-gauge railroads in connection with their various enterprises.

In January 1891, William and Austin Mitchell visited Albuquerque and stated their intention to erect sawmills on their property and enter into the manufacture of lumber on a large scale. They inspected their holdings in May to select sawmill and planning mill sites and mentioned a railroad "to connect the mills with the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad" for the first time. Later, in August 1891, the Zuni Mountain Railway (ZMRy) Company was incorporated in the New Mexico Territory, and an agreement was made with the A&P regarding the construction of the Zuni Mountain Railway in December 1891. The agreement provided that the A&P would construct the ZMRy in exchange for an unknown arrangement of payments.

Work began on the new sawmill in February 1892, and H.O. Bursum loaded his grading outfit on the cars at Albuquerque for the trip west to the work site. Work on the new railroad began immediately upon his arrival. By this time, the mill site on the A&P was known as Mitchell, which was 112.5 miles west of the beginning of the A&P track at Isleta. A well was drilled at Mitchell, and work began on a large dam and reservoir about seven miles to the south in Cottonwood Canyon.

While the A&P was more than an interested bystander in the Mitchell Brothers project, the mainline railroad played various roles in the enterprise. S.M. Rowe, one of A&P's civil engineers, laid out and surveyed the route of the ZMRy. A&P crews were involved in the construction of the ZMRy, for which the A&P also provided the rails. The A&P took a mortgage on the entire railroad for $19,200 in return for providing 550 tons of second-hand steel rails.

When the Mitchell brothers purchased the New Mexico timberland, they were experienced lumbermen who knew how to run sawmills and narrow-gauge railroads used to transport logs to the mills. Records indicate that the brothers had operated several narrow-gauge railroads in connection with their various enterprises.

In January 1891, William and Austin Mitchell visited Albuquerque and made it clear that they intended to erect sawmills on their property and enter into the manufacture of lumber on a large scale. They inspected their holdings in May to select sawmill and planning mill sites and mentioned a railroad "to connect the mills with the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad" for the first time. Later, in August 1891, the Zuni Mountain Railway (ZMRy) Company was incorporated in the New Mexico Territory, and an agreement was made with the A&P regarding the construction of the Zuni Mountain Railway in December 1891. The agreement provided that the A&P would construct the ZMRy in exchange for an unknown arrangement of payments. Work began on the new sawmill in February 1892, and H.O. Bursum loaded his grading outfit on the cars at Albuquerque for the trip west to the work site. Work on the new railroad began immediately upon his arrival. By this time, the mill site on the A&P was known as Mitchell, 112.5 miles west of the beginning of the A&P track at Isleta. A well was drilled at Mitchell, and work began on a large dam and reservoir about seven miles to the south in Cottonwood Canyon.

The active involvement of the A&P Railroad Company in the Mitchell Brothers' project was more than that of a mere observer. S.M. Rowe, a civil engineer, surveyed and mapped the ZMRy route, and A&P crews were engaged in constructing the ZMRy using A&P-provided rails. In exchange for 550 tons of second-hand steel rails, the A&P obtained a mortgage for the entire railroad valued at $19,200. Additionally, the A&P reportedly provided some freight rate concessions and agreed to purchase ties and timbers from the Mitchell Brothers.

An article published in the Albuquerque Daily Citizen in 1892 provides compelling insights into the Mitchell Brothers' lumbering operation in New Mexico, including the progress and setbacks encountered. Construction work began in May, and Sawmill No. 1 was soon operational. The 36-inch gauge railroad was extended to the impressive Cottonwood Canyon dam, and track-laying had commenced. A narrow-gauge locomotive arrived from Mitchell, Ohio, on May 21 and was placed on its rails the following day. The Shay-patent gear-drive locomotive, built in Lima, Ohio, commenced hauling logs at a rate of half a mile per day, ushering in a new era in New Mexico's logging industry.

In the last week of June, the sawmill became operational, with the sound of saws and hammers filling the air. The reservoir at Cottonwood Canyon was completed, and water began flowing through a pipeline parallel to the railroad, supplying the mill's boiler. With the arrival of T.J. Fitzgerald from Michigan as the new general manager of the operation, plans were made to add a second sawmill section, a planing mill, and a sash-and-door factory. The railroad was set to be extended from the reservoir to Rice Park, where the Mitchell Brothers aimed to establish a thriving timber industry.

The Mitchell Brothers' presence in New Mexico grew, with the emerging community petitioning for a new voting precinct to be established. Meanwhile, the sound of the locomotive hauling logs echoed through the woods, and the sawmill operated around the clock, producing lumber in high demand.

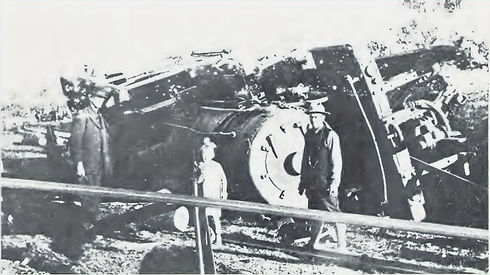

However, the company faced a potential disaster when their only locomotive was destroyed in a wreck in the woods. The accident occurred on a temporary spur where the steep grade, sharp curve, and wet track combined to derail the locomotive, dragging three loaded cars of logs along with it. The engineer, R.W. Ryan, was seriously injured, and the locomotive was reduced to a wreck. A new locomotive had to be ordered, arriving on August 18, after which the brothers resumed operations. However, in mid-September, they abruptly shut down and returned to Michigan, leaving the future of their operation in New Mexico uncertain.

The reasons for the shutdown of Mitchell Brothers' enterprise in New Mexico are not entirely clear. However, it is believed that the failing national economy and the company's inability to provide lower freight rates to the lumber markets may have contributed to it. Also, competition from the Arizona pine region could have played a role. Despite the hopes expressed from time to time, Mitchell remained a ghost town after the shutdown. The company's assets were systematically removed, including machinery and railroad tracks. Some of the mill machinery may have gone to J.M. Dennis, who was relocating his logging operation to Williams, Arizona. The A&P repossessed the railroad tracks, and one of the locomotives was found later in Mexico. Nevertheless, Mitchell Brothers retained a clear title to an impressive empire of 292,625.63 acres of well-timbered land, which became the foundation of another lumbering enterprise, the Total 317,388.81. The surviving business records suggest that the brothers orderly withdrew from their New Mexico enterprise, releasing the $478,000 mortgage held by the A&P on February 28, 1893, upon an unknown arrangement. They also conveyed back to A&P some 22,565.88 acres of land.

Albuquerque Lumber cO.

1893-1914

Railroad logging returned to the Zuni Mountains many years after the Mitchell Brothers debacle. The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad played a crucial role but became outdated during the 1890s. In 1893, the railroad was put into receivership and reorganized as the Santa Fe Pacific Railroad (SFP) in 1895. The SFP's long single track from Isleta Junction below Albuquerque to California was essential to transcontinental railroading.

In 1897, the AT&SF, the parent company of the SFP, traded with the Southern Pacific and acquired the Needles to Mojave, California, line. This completed their rail line into California and allowed for the much-needed modernization of the SFP. The rebuilding of the roadbed, track, and rolling stock began immediately. During 1903, SFP's railroad operations merged with those of the AT&SF. A revitalized primary line connection, especially one extending from Chicago to Los Angeles, was crucial to the rebirth of the lumber business in the Zuni Mountains.

Another group of midwestern businessmen brought the second large-scale lumbering in the Zuni Mountains. The investigation and necessary contacts must have been made during 1901. The American Lumber Company was incorporated on December 20, 1901, under the laws of New Jersey. Shortly after that, on December 30, the American Lumber Company purchased the remaining New Mexico timber lands from Austin W. Mitchell and William W. Mitchell. The total area was slightly over 292,000 acres. The relationship to the more significant purchase was as follows:

Original Mitchell purchase from A&P - 314,668.37 acres

Other purchases - 2,720.44 acres

Total - 317,388.81 acres

Reconveyed to A&P - (25,565.88) acres

Conveyed to Bluewater Land & Improvement Co. - (2,197.30) acres

Net sale to American Lumber Company - 292,625.63 acres

In the early 1900s, the American Lumber Company embarked on an acquisition campaign to purchase land for its operations. Among the properties procured was a 9,000-acre tract of land in the Zuni Mountains near Gallup, New Mexico. The American Lumber Company purchased the property for $1,100,000. It was subject to two mortgages held by the Mitchells, one from the McKinley Land and Lumber Company and the other from 1902.

Following the timber purchase, the American Lumber Company turned its attention to other aspects of the business. The company was tasked with finding a suitable site for its sawmill. A location with convenient access to the AT&SF mainline and a reliable water supply was essential. Additionally, an area in or near a town with a sufficient labor supply would be advantageous. Negotiations with AT&SF were conducted to determine freight rates for both logs and finished lumber. Finally, arrangements were made for the construction of the logging railroad and woods camps for the loggers.

In early 1903, the company selected a 110-acre site in northwest Albuquerque as the site for its sawmill. The site was generously donated to the company and was chosen due to its abundant water supply and proximity to an ample supply of labor and the necessary housing and amenities. Contrastingly, the woods crews in the Zuni Mountains would be residing in a remote area under extremely primitive and lawless conditions. Furthermore, Albuquerque offered excellent transportation options for finished lumber products with mainline railroads extending north and east, west, and south.

Construction of the sawmill began early in 1903 and was reported as nearly complete in July of that year. The sawmill was the central structure of an imposing collection of sturdy buildings. The sawmill was a wooden building measuring approximately 208 feet in length by 66 feet in width. It was three stories in height and made with 14-inch square hard pine timbers supporting the first level and 12-inch square timbers for the second and third levels. Power for the saws was transmitted by shafts and wide leather belts. The main drive shaft, 6-7/8 inches in diameter, was rotated by a 48-inch-wide double leather belt from the adjacent powerhouse. The belt was 190 feet long.

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, the American Lumber Company constructed a sawmill complex with several structures, including a brick building that measured 93 feet by 50 feet. The building had 21-foot-high walls and a galvanized iron roof. Power for the sawmill was generated by four boilers, each 18 feet in diameter and 72 feet long. The boilers had an output of 225 horsepower, and steam was used to power the sawmill machinery.

The main engine used in the sawmill was a Corliss reciprocating engine with a 20-foot diameter flywheel. The engine was designed to even out the power flow, which was essential for the proper functioning of the sawmill. Additionally, there was a refuse or sawdust burner that measured 32 feet in diameter and was fully 100 feet high. The complex also had plans for several additional structures, including a planning mill, box factory, dry shed, and drying kilns.

The sawmill complex had open spaces for drying and storing lumber and a large timber dock that measured 100 feet by 80 feet. The sawmill designer and builder was Harry Badstubner of Texarkana, Arkansas. He was responsible for creating a state-of-the-art sawmill crucial to the American Lumber Company's operations.

The AT&SF railway company played a significant role in the American Lumber Company's business. The logs were loaded onto the lumber company railroad in the woods and transported in trainload quantities to Albuquerque. The AT&SF built a mile-long spur line just north of Albuquerque to bring the logs to the sawmill. The AT&SF yard engine added the sawmill, switching to its daily routine. The company also provided empty log cars for lumber shipments. It was responsible for returning empty log cars to the woods.

The American Lumber Company also built a logging railroad in the Zuni Mountains, southwest of Albuquerque. The Zuni Mountain Railway was a standard gauge logging railroad that extended approximately 14 miles, with several miles of spur lines feeding the main line. The railroad was built southwest of Thoreau, which was a junction on the SFP mainline named Mitchell. The railroad was pushed south into the Las Tuces Valley and beyond into Cottonwood Canyon. The completion of the railroad took up most of 1903.

Two locomotives were purchased for the Zuni Mountain Railway. The locomotives were sourced from used railroad equipment dealers. The first locomotive, ZM No. 2, was a small locomotive, and little is known about it. The second locomotive, ZM No. 4, was an ancient 4-6-0 or ten-wheeler type. One hundred wooden log cars were built for the Zuni Mountain Railway at the American Car Company in Mt. Vernon, Illinois. These cars were equipped for mainline operation over the AT&SF between Thoreau and Albuquerque.

Two steam slide-back log loaders were purchased in 1903. The steam slide-back log loaders were used to load logs onto the train cars for transportation to the sawmill. Essentially, the steam slide-back log loaders were a light steam donkey engine on a sturdy wooden sled with a rigid boom at one end. A wooden plank housing covered the boiler and donkey engine. The loader was slid along from car to car using a cable and winch.

The connection between the woods and the sawmill was maintained by AT&SF. The loaded and empty log cars were transported by AT&SF as per the terms of the contract between the lumber company and the railroad. The contract defined the specific terms and conditions of the log train movements and set the rates charged to the lumber company.

The new sawmill was a significant boost to Albuquerque's economy, and its citizens were very interested in it. To showcase their new plant, the American Lumber Company hosted a reception and dance on the night of July 23, 1903. The event took place on the mill's second floor, where the First Regiment provided music, and refreshments were served.

By October, everything was ready. The company had 1500 workers, and timber was stacking up in the mountains. The first train of logs was loaded up and sent down the track to the junction. It arrived in Albuquerque on October 25, 1903, and was immediately switched to the sawmill. Sawing began the next day.

It was evident at this point that the American Lumber Company was not just a temporary arrangement. The company had invested two million dollars in real estate and facilities, and the construction had been pushed through quickly. A solid collection of lumbermen and businessmen was in charge, including officers like C. A. Ward, T. E. Terrepin, and A. M. Trumbull. The operating personnel included Ira B. Bennett, F. W. Decker, T. W. Tiest, G. A. Welch, J. E. Brayton, and George K. Davis.

During 1904, the company continued to expand its operations. At Albuquerque, the mill complex grew to include a planing mill, which produced moldings and fed a box factory and a sash-and-door factory. Additional roll sidings were built to ship the new products to the market.

The logging camp in Kettner witnessed the growth of a town that accommodated the increasing population by expanding its services and facilities. On January 23, 1904, the post office opened for business with Stanleigh A. Horabin as the postmaster. Horabin also operated the commissary or company store, in partnership with A.B. McGaffey, who later transitioned to the logging business in the Zuni Mountains.

It is worth noting that Kettner derived its name from a homesteader in the district. However, the town was frequently misspelled as "Ketner". The official documents of the American Lumber Company spell it as Kettner.

The American Lumber Company encountered difficulties in limiting the timber cutting to their odd-numbered sections. Survey lines were not always clearly marked, and the temptation to continue logging across the line was high when encountering a good stand of pine. Moreover, harvesting the timber on the even-numbered sections would allow for carrying more logs by a given length of railroad. Consequently, in November and December 1904, the company entered into several contracts with the Territory of New Mexico, paying $2.50 per acre for the right to cut trees on the even-numbered sections. These contracts covered about 34,000 acres or over 53 sections.

Given the logging activity's remote location and the dearth of business records, it is difficult to determine the construction date of a particular logging railroad line. However, periodic reports of the company's overall activities reported changes from the preceding period. One such report in August 1905 indicates that the railroad operations had grown by one locomotive and 30 log cars, bringing the total to 3 locomotives and 130 log cars.

During the summer of 1905, the American Lumber Company purchased a new locomotive from an equipment dealer in Chicago. As ZM Number 6, it became the "mainline" lokey, hauling trains of logs from Kettner to Thoreau and returning with the empties. This regular run included a caboose, carrying passengers, supplies, and the train crew.

The American Lumber Company utilized woods railroads to transport logs from the rougher terrain. In early 1906, the company placed an order for a new 50-ton Climax-type gear drive locomotive from the Climax Manufacturing Company situated in Carry, Pennsylvania. This new locomotive was designated ZM Number 8. The locomotive's three independent trucks provided greater flexibility on rough tracks and sharp curves, while all the weight on the driving wheels enabled it to pull more on steep spur lines, resulting in reduced costs as the ZM tracks extended further into the woods. In 1908, the company ordered another locomotive, Number 12, which was even larger than its predecessor, weighing about 133 tons with its tender. The locomotive alone weighed around 84 tons. The advent of No. 12 on the main line log run from Kettner to Thoreau necessitated some hurried trackwork to keep it on the rails. The two new locomotives were put to work in mid-February of 1908 after a winter shutdown. The American Lumber Company was not substantially affected by the series of lawsuits filed by the United States Government in October 1907 alleging fraudulent purchase of timberlands from the Territory of New Mexico by several lumber companies. In April 1908, the American Lumber Company was at the peak of its growth and was operating the longest and busiest railroad of its life, sending between 30 and 40 carloads of pine logs to the mill every day.

The American Lumber Company operated a railroad with 55 miles of track, 6 locomotives, and 160 logging cars. They had a "roundhouse" and machine shop located at Kettner for maintaining the locomotives. The decrease in the number of ZM log cars from 200 to 160 may have been due to the increasing use of AT&SF steel flat cars of Class Ft-G. These cars were suitable for the long, fast main-line haul from Thoreau to Albuquerque and were equipped with cross-bunks and chains for the logging trade. The ZM track included numerous loading spurs and a long main line running southeast along the Aqua Fria Valley to Paxton Springs. The company was running three logging camps in addition to Kettner, the headquarters camp, and over 500 men were employed in the woods.

To make the task of building railroad roadbeds and laying track to the cutting areas easier, the American Lumber Company followed the typical practice of constructing their logging grades well before the loggers reached a given area. This allowed the surveyors and grading crews to work in favorable weather and at their own pace without delaying the loggers. For short-lived spurs, little more than the clearing of the surface and the leveling of the bed itself was required, while main routes involved more permanent construction techniques such as rock embankments and the moving of a lot of fill dirt.

The American Lumber Company often logged much of an area and yarded the logs to decks along the line of the projected railroad before actually laying track into the area. Once the track had been laid into an area, logs could be loaded fairly rapidly using the steam loaders. The woods locomotives, usually the Climax or one of the two Shays, would make several trips out on the spurs each day to keep the loaders supplied with empty cars and to take the loads into the main camp.

In countries with unfavorable conditions, constructing logging spur tracks required complex techniques. One of the methods that proved effective was the use of timber cribbing, a technique that involved using timber to build temporary railroads across streams, drainages, and minor depressions. In the Zuni Mountains, cribwork structures were used not only as trestles over streams but also as fills across side valleys and low spots in the desired grades. These structures, commonly referred to as "pigpen trestles," had the advantage of utilizing locally available materials and requiring minimal skill to be built.

Hand-built stone and earth fills or framed timber trestles were alternative methods used in constructing logging spur tracks. However, both methods were deemed expensive for the short life and light trains of the logging spurs, thus making cribwork structures the preferred option for building temporary railroads.

A valley tributary to Bluewater Creek features several cribwork crossings of the mainstream and side valleys on the spur line railroad that runs up the valley. Around 20 log structures were erected in a two-mile section of the line, most likely in the later years of operation, circa 1910-1913. The railroad spur was built to transport timber logged from the eastern region of Rice Park and below the northern rim. The logs were transported down several valleys and were loaded onto log cars stationed at various points along the railroad spur. The longest distance the logs were skidded was just over a mile. The railroad line followed the stream bed, with a gentle grade that averaged around three percent, which was a relatively easy grade for the powerful gear-driven locomotives of the ZM.

According to the Albuquerque pamphlet by Hening and Johnson, the cutting of timber was done with two-man saws, while skidding and yarding were performed by crews with horse-drawn four-wheel wagons or 12-foot diameter big wheels. Logs were yarded into long rows near the railroad track for loading on log cars. Two steam loaders were used for loading, but the process was often accomplished by teams using lines to lift the log pole inclines onto the cars. The work was carried out with great efficiency despite the laborious process with little mechanized help.

Kettner was a temporary place with basic facilities, including a hotel and a commissary. There were also numerous little houses and cabins for the married men who were part of the logging company.

The Albuquerque mill plant was expanded considerably by 1908, with the addition of various factories that required much more power. There were two steam plants, each with six boilers, and three reciprocating steam engines of 500, 750, and 850 horsepower. The annual output was typically 35 million board feet, but a rate of 50 million board feet per year was reached during 1908. This impressive feat was achieved by running two shifts in the sawmill, and the company's capacities were as follows:

- Sawmill: 350,000 board feet daily (two shifts of 10 hours each)

- Moulding Mill: 100,000 feet of moldings daily

- Lath: 50,000 feet daily

- Shingles: 50,000 feet daily

- Windows: 2,000 feet daily

- Doors: 1,500 feet daily

The drying yards of the American Lumber Company reportedly held an average stock of 20 million board feet, as reported by Hening and Johnson's 1908 pamphlet and the Albuquerque Morning Journal from the same year. The company had successfully logged over 27,000 acres, including state lands in Townships R. 14 W., T. 12 N., and R. 14 W., T. 13 N. Furthermore, the company had extended the railroad to the east and up into Rice Park, which became the next district to be logged.

Despite the company's previous success, the volatile nature of the lumber business was about to impact its operations. In the summer of 1909, the company relocated its main camp from Kettner to a new site named Sawyer, which was located several miles further down the main track of the ZM. Sawyer quickly became a flourishing community in the heart of the pine forests, complete with a general store operated by the McGaffey Company and a small school.

While the move to Sawyer was successful, indications suggest that Kettner remained operational. The maintenance facilities for the railroad and machinery were still based in Kettner, even though the post office was formally transferred from Kettner to Sawyer on July 16, 1909. The American Lumber Company had remained remarkably debt-free until this point, with only a $400,000 first mortgage secured by lands on the books. However, the mortgage was due on January 20, 1912, and only two dividends had been recorded, amounting to two percent paid during 1906.

In September 1909, the American Lumber Company released $650,000 worth of first mortgage 6% serial gold bonds that would mature serially until January 1, 1922. The company was expected to contribute $2 per thousand board feet to a sinking fund to retire the bonds. This caused a significant change in the company's financial outlook, as they now had to make hefty payments at regular intervals. They had to pay $50,000 every January 1 from 1911 through 1920, as well as an increased payment of $75,000 on January 1, 1912, and January 1, 1922. Additionally, they had a $400,000 mortgage due on January 20, 1912.

Despite these financial obligations, business was good in 1909. The company reported a net profit of $100,242.42 on sales of 36,356,257 board feet, with a timber cut of 32,259,272 board feet. The logging railroad had been reduced to a length of 40 miles, possibly due to the removal of the old logging spurs north of Kettner.

In early 1910, the company ordered a new logging locomotive to complete the modernization of the railroad motive power. The new locomotive was a 70-ton, 3-truck Shay, identical to Number 10, and was delivered in May 1910. It was assigned Number 3, breaking their long-standing practice of using only even numbers on the locomotives. With this purchase, the ZM locomotive stock consisted of No. 4, which was used for construction, No. 6, which was used for construction and as a relief locomotive for No. 12, and Nos. 3, 8, and 10, which were used as woods locomotives on steeply graded spurs. By this time, old Number 2 had been scrapped.

On November 8, 1910, the American Lumber Company was reincorporated in New Mexico, with a capitalization of eight million dollars. The incorporators were E. W. Dobson, A. A. Keen, I. B. Koch, and T. J. Sawyer. It is unclear why this action was taken, but it may have been to allow or enhance the sale of company stock to the public to raise cash.

In the summer of 1910, the American Lumber Company implemented a second shift at its mill, resulting in an increase in production by almost double the rate of the previous year. The company's efforts to increase profits in order to maintain its property and pay off debts proved successful for a period. As a result, operations continued with minimal change through 1911 and 1912.

During this period, the company procured several locomotives from the AT&SF via purchase or long-term lease. One such locomotive, AT&SF Number 096, was an antiquated, lightweight 4-4-0, likely reserved for construction or switching purposes. The ZM purchased this locomotive on April 3, 1912. The company also leased two more powerful 4-6-0 locomotives from the AT&SF, namely Numbers 261 and 271. These locomotives remained in service on the ZM for several years but were rendered obsolete on the AT&SF itself.

On June 9, 1913, the company renewed its prior timber contracts with the Territory of New Mexico, this time with the State of New Mexico. Although the transaction went relatively unnoticed at the time, it was subject to scrutiny a decade later. Unfortunately, the absence of records and press reports makes it challenging to discern the specifics of the events that occurred in 1913.

By September of that year, the company had ceased all operations. On January 1, 1914, the American Lumber Company failed to make the payment due on its first mortgage bonds. Subsequent events suggest that there was a modicum of forethought behind the sequence of events which led to the company's failure. The company's activities leading up to its collapse occurred at a measured pace, and it emerged from the ordeal with a new organizational structure and a fresh infusion of capital.

Following the default, a committee of bondholders of the American Lumber Company was established to manage the company's affairs. The American Lumber Company Bondholders Agreement, dated May 25, 1914, provided the necessary means for the creditors to control the company's business.

On June 23, 1914, the American Lumber Company filed for receivership in the District Court in Santa Fe after the Detroit Trust Company started foreclosure proceedings against the company's defaulted bonded indebtedness of $500,000. The company officers had been coming and going for some time before this decision was made.

The court quickly approved the receivership petition and appointed Charles F. Wade, the former president of the company, and George W. York of Cleveland, Ohio as receivers. The court observed that the operation of the plant was not intended, which means that it was not possible to keep the company running.

In July 1914, the Federal Court authorized the issuance of $40,000 in receivers' certificates to pay taxes, insurance, back wages, and $500 a month for watchmen at the mill and at the woods facilities of the company. The American Lumber Company was essentially out of business from this point on, and its properties were idle.

The struggle to resolve the company's debts and reopen the lumbering business was a lengthy one, and it was just beginning. This event marked the end of an era for the American Lumber Company, and it had a significant impact on the local economy and the livelihoods of those who depended on the company for their jobs and income.

mCkINLEY lAND & lUMBER cO.

1915-1923

The bondholders' committee of the American Lumber Company demonstrated exceptional diligence and proficiency in managing the company's affairs. Although incomplete, available records suggest that the committee meticulously planned and executed every step of winding down the company's operations and establishing a new one.

A definitive court decree, dated July 16, 1915, granted the receivership, ordering the sale of the American Lumber Company's assets to cover its bonded debt of $546,250, inclusive of interest and expenses. The sale, however, materialized on November 11, 1916, indicating that behind-the-scenes negotiations and delicate maneuvers must have taken place.

From the onset, Otis and Company, the bondholders' agent, emerged as the buyer of the American Lumber Company's assets. The McKinley Land and Lumber Company, incorporated in New Mexico on the same day, played a crucial role in the company's revitalization. The company's principals agreed with Otis and Company to purchase the assets of the American Lumber Company, subject to court confirmation. The purchase price was $2,000 plus 60 shares of the McKinley Land and Lumber Company's stock, in addition to Otis and Company's debts and obligations incurred in purchasing the assets.

Currently, the property in question comprises the Albuquerque mill site, factories, equipment, lands, and the Zuni Mountain Railway, covering an area of 115 acres. According to the inventory conducted in 1916 by the American Lumber Company, the lands were classified as follows:

Original Mitchell Purchase (226,719.16 acres)

Day or Foster Purchase (10,796.74 acres)

Territorial Purchase (3,966.43 acres)

Soldiers & Homestead Scrip Filings (520.38 acres)

Patented Land, Mitchell Purchase, amounting to a total of 242,478.01 acres.

The inventory of the Zuni Mountain Railway, documented in The Timberman (1917), included the following details:

Fifty-five miles of standard gauge rails weighing 60 to 75 pounds per yard, three geared and 2-rod locomotives, 158 logging cars, 20 flat cars, two gas speeders (motor rail cars), and two donkey engines (loaders).

The figures above indicate the number of operational locomotives, as the records demonstrate that the company owned at least five-rod locomotives. The American Lumber Company receivers had purchased the two old AT&SF 4-6-0 locomotives, namely Nos. 261 and 271, on March 1, 1916. Therefore, the total locomotive roster included the following:

Numbers 3, 4, 8, 10, 12, 096, 261, and 271.

On January 15, 1917, the American Lumber Company completed the transfer of its properties to the McKinley Land & Lumber Company. The latter acquired the real estate, while Otis & Company received the outstanding $445,000 owed to the old bondholders, in addition to interest, costs, and the agreed-upon fee.

At the time of the transaction, McKinley Land & Lumber Company's backers were disclosed as George E. Breece and the West Virginia Timber Company (WVT). WVT held most of the stock of McKinley Land & Lumber Company, and Breece served as the president of WVT. As the rehabilitation financing of the New Mexico properties was organized, the two companies' executives became closely intertwined.

George Elmer Breece soon became a crucial figure in New Mexico's lumbering industry. He was born in Roundhead, Hardin County, Ohio, in December 1864. As a youth, Breece worked in a sawmill, acquiring the skills of a sawyer, block setter, and saw filer. As a young man, he became the superintendent for the Advance Lumber Company of Cleveland, Ohio, before relocating to Charleston, West Virginia. Breece flourished as a lumberman during his tenure in Charleston and ultimately became the president of WVT, headquartered in that city. Around 1907, Breece visited New Mexico on behalf of the Advance Lumber Company, and he presumably familiarized himself with the lumber business in New Mexico during the ensuing years.

The commencement of World War brought the logging operation at Zuni Mountain to a temporary standstill. The U.S. Army Signal Corps called upon Breece to assist in the spruce logging effort in the Northwest, where high-quality spruce timber from the western slopes of the Coast Range was the primary structural material for airplanes that were urgently needed in Europe. Breece's commendable efforts led to his promotion to the rank of Colonel before his return to New Mexico.

After the cessation of the World War, the situation in New Mexico started to pick up. In May 1919, McKL&L dispatched two experienced personnel to survey the woods. One was Noah Moore from Charleston, West Virginia, and the other was Charles H. Wade, who had been with the American Lumber Company since its inception. However, Wade passed away in an Albuquerque lunchroom before he could make it to the mountains.

Moore traveled to Thoreau to examine the railroad and assigned a crew to repair the track between Thoreau and Sawyer. Despite the rail track being overgrown and obstructed by logs and trees, it was in good enough condition to be prepared for hauling logs within a few weeks.

Moore also hinted in the local press about another matter concerning McKL&L - the freight rate charged by AT&SF for transporting logs from Thoreau to Albuquerque. The issue remained unresolved until Breece's arrival in early June to initiate negotiations with the AT&SF.

The sawmill and plant facilities were scheduled to commence operations on September 1, 1919. The refurbishment of the mill involved minimal heavy work, albeit improvements were made to the lumber storage arrangements. In the woods, 75 men were engaged in railroad operations, either cutting ties or logging in preparation for the onset of periodic log shipments around August 1).

Improvements to the logging equipment in the mountains were anticipated to decrease logging costs. Specifically, a new American Hoist & Derrick Company Model C log loader was procured for $8,250.00, with the addition of freight. Furthermore, six Caterpillar tractors were acquired for skidding logs to the railroad.

The woods railroad continued to operate out of Sawyer, leveraging the two 70-ton Shays and 50-ton Climax locomotive. During the rehabilitation of the property, substantial repairs were made to the Climax. Additionally, two or three-rod locomotives were repaired for use on the primary line haul from Sawyer to Thoreau. Although relatively modern and little used, the heavy 2-8-0 Number 12 was sold in 1920. In its place, an old 4-6-0 from the defunct Colorado Midland (CM) was acquired around the same time.

The McKinley Land and Lumber Company (McKL&L) placed a significant emphasis on the acquisition of timber. Before resuming its logging operations, the company invested in additional timberlands from the State of New Mexico. On August 6, 1918, McKL&L purchased a significant amount of state land, totaling 39,974.54 acres, at the cost of $3.00 per acre. This acquisition effectively consolidated a substantial amount of timberland in the Zuni Mountains that the company did not previously own.

Following this Purchase, McKL&L owned an estimated 550 million board feet of timber on its lands and rights to 450 million board feet of timber on state lands. When cut, the company agreed to pay $2.15 per thousand board feet for the state timber. However, the expenses associated with refurbishing the railroad and sawmill and acquiring additional lands resulted in the company accumulating debts.

To address these debts, McKL&L issued a bond of $550,000 of seven percent first mortgage bonds in June 1919. The bond was to be paid from a sinking fund set aside at $2.50 per thousand board feet shipped from the mill. Additionally, the bonds were guaranteed by the West Virginia Timber Company.

During 1920, McKL&L maintained a timber-cutting rate of approximately 35 million board feet annually. The company continued to purchase more timber and lands, including a transaction in June 1920 in which it acquired 530,000 board feet of timber in the Zuni National Forest. This tract was located in Cottonwood Canyon, south of Thoreau, and the company's cutters began working on the new Purchase immediately.

In July 1920, McKL&L initiated another agreement with the State of New Mexico by acquiring an additional 700,000 acres of land and the rights to timber on 100,000 acres. Despite the lack of transparent reporting on the transaction terms, it is worth noting that the land was priced at $3.15 per acre. At the same time, payments were made monthly for the land and timber.

The extended log haul over the AT&SF to Albuquerque proved a significant challenge for Breece and McKL&L. In October 1920, AT&SF announced an increase in its freight rate for the long haul from $2.50 to $3.12-1/2 per thousand board feet. Breece, in response, voiced his concerns in the local press and highlighted that McKL&L had invested $100,000 in improving the Albuquerque sawmill based on the AT&SF's agreement to continue the lower rates. Additionally, the company filed a formal protest with the New Mexico Corporation Commission. The AT&SF, however, proceeded with the higher rate thirty days after giving notice, despite the protest.

The primary logging camp was moved from Sawyer to Breece in 1920 or 1921. Breece was situated in the Los Tuces Valley, east of the earlier cutting areas. The company served a network of steeply graded logging railroads on the slopes facing the Los Tuces Valley.

The newly established logging district was situated north of the previously utilized areas. The region's topography was steeper and broken, necessitating logging railroad spurs with more curves and generally steeper grades. The three geared locomotives were well-suited to these conditions and continued to play an essential role in the logging operations. On the "mainline" side of Breece Company, several rod locomotives pulled log trains to Thoreau. One of these locomotives was the former Colorado Midland 4-6-0, while the others were likely survivors from the American Lumber Company. Although these locomotives were outdated, they remained suitable for the logging rail road's light rails and uneven track.

All of the McKL&L locomotives were considerably worn out by this time. As a result, the decision was made to acquire new locomotives as replacements instead of rebuilding the outdated machines. In August 1922, a new locomotive that differed significantly from any other locomotive on the railroad was purchased. It was neither an outdated mainline type nor a complex gear drive locomotive. The new locomotive was an H. K. Porter Company-built heavy rod-type locomotive that combined small 44-inch diameter drive wheels with large cylinders, resulting in a highly powerful locomotive. Moreover, the locomotive carried its fuel and water in tanks on the main frame, eliminating the need for a separate tender. The new Number 6 locomotive, featuring the 2-6-2 wheel arrangement, was highly suited to both the steep woods spurs and the main line.

The Number 6 locomotive, despite its somewhat unusual features, proved to be a success on the McKL&L lines. As a result, a nearly identical locomotive was purchased in June 1923, known as Number 7, which only differed from Number 6 in having slightly larger cylinders. After the second new Porter locomotive arrived, it seems the old 50-ton Climax and the old American Lumber Company locomotives were retired.

In a recent transaction, the Climax locomotive, which had been aging, was replaced by a robust rod locomotive that was acquired from the defunct Colorado Springs & Cripple Creek District (CS&CCD) Railroad. the following locomotives were utilized by McKL&L during the period from 1922 through approximately 1924:

- Number 3: 3-truck, 70-ton Shay

- Number 6: 2-6-2T, H.K. Porter

- Number 7: 2-6-2T, H.K. Porter

- Number 8: 2-truck, 50-ton Climax, retired in 1923

- Number 8: 2-8-0 from CSSCCD, purchased in 1923

- Number 9: 4-6-0 from CM, retired around 1923

- Number 10: 3-truck, 70-ton Shay

An intriguing event occurred in October 1923 that may have contributed to the retirement of the remaining old American Lumber Company rod locomotives. On October 16, C.G. Austin and Phillip Honea, a fireman, and a brakeman, respectively, were severely scalded when locomotive Number 6 and four loaded log cars collided with their locomotive near Buck Moore's logging company. According to news reports, the collision resulted from hostility between Slim Dentlin, the engineer of Number 6, and the crew of the other train. Dentlin allegedly released his engine and train to collide with the train that carried Mustin and Honea. Mustin's locomotive was completely destroyed.

Despite the continued success of their lumbering business, McKL&L faced challenges due to their vulnerability to freight rate increases by the AT&SF and complex issues with timber contracts with the State of New Mexico. Each of these difficulties was addressed distinctly.

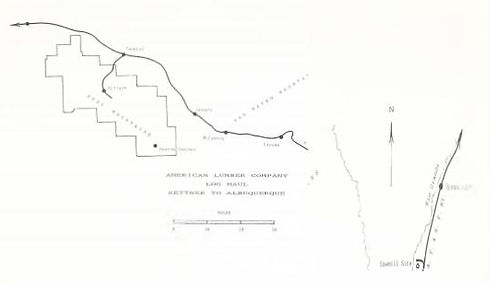

In 1922, the AT&SF imposed exorbitant freight rates for log hauls, prompting the McKinley Land & Lumber Company (McKL&L) to explore reducing operation costs. During the Board of Directors' Meeting on December 26, 1922, the company resolved to set aside $250,000 from its surplus earnings to construct a new railroad from Grants, New Mexico, to the company's timberlands. The proposed 50-mile-long rail system was critical to the company's continued operations. By relocating the rail connection with the AT&SF from Thoreau to Grants, the company could reduce the log haul over the big carrier by 29.2 miles. The directors suggested that the new rail system could be independently incorporated and named the 'Grant and Southeastern Railroad' if it fit. Despite revealing its intentions to construct the new rail system, the company only took significant steps towards its realization several years later.

In 1923, issues concerning logging on state lands became more pronounced. The Land Commissioner twice declined to accept payment from McKL&L for timber cut on state lands under the 1904 contract, first in May 1922 and then in February 1923. The contract, initially between the American Lumber Company and the Territory of New Mexico, was extended on July 19, 1913, and was due to expire on June 1, 1923. The issue surrounding this matter involved several factors, including old land lawsuits of 1907, fair prices, bidding methods, and similar concerns. Eventually, on September 1, 1923, the attorney general advised the Land Commissioner to accept the checks from McKL&L, and the contracts and extensions were validated accordingly.

In the subsequent year, George E. Breece restructured his business holdings by consolidating them into a single corporation, the new George E. Breece Lumber Company.

George E. Breece Lumber Co.

1924-1931

Prior to 1924, George Elmer Breece had assumed an increasingly influential role in numerous lumber companies in which he had invested. These companies included the West Virginia Timber Company, O.S. Hawes Lumber Company, Grayling Lumber Company, Porter Lumber Company, White Pine Lumber Company, and McKinley Land and Lumber Company. Breece held varying levels of interest, ranging from stock ownership to serving as president and general manager.

In 1924, a new entity named the George E. Breece Lumber Company (GEBLbr) was established to oversee the Breece interests. The firm was incorporated in New Mexico in June of that year. On August 1, 1924, GEBLbr merged the West Virginia Timber Company and the McKinley Land and Lumber Company, though both companies maintained their respective names for a period of time.

Regarding the logging railroads in the Zuni Mountains, the change was merely nominal. Operations continued on the Thoreau railroad, and the Albuquerque sawmill maintained an annual production rate of roughly 30 million board feet. The railroad operated five locomotives, owned 55 miles of track, and the primary logging camp remained situated in Breece.

A 1983 cultural resources survey in connection with the Bluewater Timber Sale revealed several trestles along a logging railroad spur erected by the George E. Breece Lumber Company circa 1924-1925. The spur extended more than two miles across the northern portions of Sections 23 and 24, T. 12 N., R. 13 W., on an unnamed mesa east of Pine Canyon. The area gradually slopes northeastward toward the Las Tuces Valley and Bluewater Lake.

The pathway connecting the line to the spur ascends through a shallow ravine traversing Sections 14 and 23. The roadbed, replenished with earth, is bordered with local rocks, meticulously laid up to form a low wall. The turnout or switch to the spur is easily recognizable through its diverging border walls, forming a distinct shape of a railroad turnout. A shallow culvert, constructed in the same manner as the roadbed, i.e., by laying loose stones on the ground, serves as a water crossing near the turnout. The culvert's roof may have consisted of timbers.

Above the switch site, three pits were excavated, one of which appears to have served as the foundation for a small shed or tool box. The central pit, occupying an area of approximately 12 square feet, comprises sides lined with rocks that are carefully stabilized. This location offers possibilities for various activities, such as storing track tools and hand cars for railroad maintenance crews or fire-fighting tools and supplies. The use of movable sheds or tool boxes would have allowed for the smooth movement of equipment as logging progressed.

The spur line originating from the switch made a curve towards the east and followed a consistent elevation contour along the slope. The roadbed gradually became shallow and consisted of a single line of rocks along the lower side. The remaining crossties indicated that only a few inches of local sandy topsoil were used to construct both the roadbed and the ballast for the track. The ballast, being the compacted material that surrounds and supports the crossties, serves the purpose of draining the crossties and distributing the weight of the trains over the entire area of the roadbed.

The spur line is identified by six water crossings spaced out along its length. Within the first half-mile, two shallow culverts were constructed to facilitate the flow in small gullies. The first culvert was built using rocks in a rectangular pattern, forming an opening only slightly wider and deeper than the normal spacing between crossties. The second culvert was made using logs to form the opening between the ties.

The railroad, as it progressed along the slope, encountered four deeper gullies or ravines within about a mile. At each of these depressions, a cribwork timber trestle was built in place of an earth or rock fill with a culvert opening. These trestles, constructed in succession, share many common details and may be described as a group. A summary of the overall dimensions and major characteristics of these trestles are listed in the image to the right.

Upon close examination of the trestles, several noteworthy observations were made. The primary longitudinal stringers all measure between 15 to 16 feet, similar to typical saw logs loaded onto railroad flat cars. Additionally, lateral spacing is in close proximity to 56-1/2 inches, which is consistent with the gauge (distance between rails) of the railroad track. This particular dimension facilitated the use of standard crossties on the bridges as opposed to the much heavier "bridge ties" utilized where the stringers are set apart at greater distances.

Further along the line, between two simple culverts, evidence of a derailment was detected, which had caused significant damage to at least one log car. Several parts of the car were discovered in the area, including a log bunk cheese block, a truck spring, and a stirrup step hanging from a tree limb. An unusual length of rail and secondary growth characteristics consistent with disturbed ground completed the overall scene.

The logging spur under discussion has several parts where its roadbed has vanished entirely. Only by following the occasional lines of rocks and the few remaining crossties can the path be traced, and only where the roadbed received more substantial grading is the line discernible with certainty.

It was not feasible to trace the full length of the Pine Canyon spur on foot due to time constraints. However, a later review of Forest Service aerial photographs indicates that the spur may have extended as far as Section 25, T. 12 N., R. 13 W.

A considerable area, possibly three or four square miles, was tributary to the railroad. Tractors or large wheels pulled by horses could have easily skidded logs down the open slopes to the spur line. This area extended south to the ridgeline and east to Bluewater Creek.

The construction of the new logging railroad westward from Grants, New Mexico, was long-planned and began in early 1926. The route crossed the lava country west of the town, entered Zuni Canyon, and followed a winding path along the canyon floor before reaching Malpais Spring. The rails proceeded up La Jara Canyon and over a low summit, ultimately entering the valley of Agua Fria Creek near Paxton Springs. A few short branches or spurs were constructed, and a long line extended northwest along the Agua Fria Valley. Reports suggest that 15 or 20 miles of new railroad were constructed during 1926.

During the summer of the same year, GEBLbr procured the Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Company situated in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico. Subsequently, the organization initiated the development of a new sawmill in Alamogordo, which was completed along with an expansion of the Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Company's railway network in early 1927. Additionally, Breece divested his interests in the Porter Lumber Company and the White Pine Lumber Company during the month of July in 1926.

In the summer, GEBLbr acquired the Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Company in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico and built a new sawmill at Alamogordo. By 1927, the company had mortgaged nearly all of its sawmill and timber properties to finance its expansion. The company used sinking funds to determine payment schedules, paid at $2.00 or $2.50 per thousand board feet.

A new logging railroad was operational in March 1927, but a fire damaged the roof of the roundhouse and machine shop at Grohts, and two locomotives were also damaged. However, they were quickly repaired. The Grohts railroad went into operation in 1927, and the rails were removed from all the lines out of Thoreau shortly after that.

The logging industry in the Zuni Mountains has shifted, relying more on trucks than on the railroad to transport the logs. As a result, the railroad is no longer required to run to every logging area.

After a quarter-century of intensive logging activity, timber in the Zuni Mountains has become scarce, prompting George Greece to explore new prospects for future timber. He proposed a plan to log the New Mexico Division of the Apache National Forest, a region concentrated in the Gallo Mountains in western New Mexico.

The present text is a report on a logging railroad project proposal outlined by Logging Engineer D. M. Long. The proposed railroad is envisioned to extend south-southwest from the end of the Grants railroad towards Quemado and into the wooded area. The project requires 190 miles of track to reach all the areas under consideration. However, the cost of constructing such a railroad project was deemed to be far more than the area's relatively small amount of timber could pay for. Long's recommendation was to cut the timber through a series of small mill sets and haul them to the railhead by automobile trucks.

Although the Grants railroad and the Albuquerque sawmill continued to operate, the company's logging railroad at Cloudcroft was shut down permanently in June 1930, and the Alamogordo mill closed for some time.

The company's operations during 1931 were reduced, and wages had been cut by 20 percent when operations resumed in September. The company realized that it was spending a vast amount of money in the woods, so it leased out the logging work to two businessmen, M. R. Prestridge and Carl Seligman.

I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

Prestridge & Seligman

1931-1942

During the 1930s, Carl Seligmon and M.R. Prestridge assumed ownership of the Bernalillo Mercantile Company, a general merchandise enterprise with retail outlets in Bernalillo and Grants, New Mexico. The two men formed a partnership. Prestridge and Seligman took control of the logging operations in the Zuni Mountains, which the George E. Breece Lumber Company had previously controlled.

Prestridge and Seligman (PCS) took over the GEBLbr Company railroad in its then-current state. They initiated logging operations using the Breece rolling stock, which had already begun to show signs of wear and aging. A few months into the operation, P&S procured their first locomotive, a small 2-6-0 type, from The Glover Machine Works, a relatively unknown machinery builder in Marietta, Georgia. Despite the locomotive's acquisition, it proved to be undersized for the required work and was sold in April 1935.

P&S obtained a new locomotive, No. 648, a large 2-8-0 purchased from AT&SF in June 1934. This Baldwin freight locomotive was previously used in the Raton area. A heavy 130-ton 3-truck Shay-type locomotive was acquired from the Southern Iron & Equipment Company by P&S in April 1935. These locomotives were well-suited for the job, but the track on GEBLbr lines had to be strengthened to accommodate them.

In 1934, Prestridge and Seligman were employed at Paxton Springs, where approximately 100 men worked. They used horse logging to move the logs to the railroad. The lumber business was uncertain at that time, and a brief shutdown of the GEBL sawmill in July 1934 caused 5 million board feet of logs to be stacked along the logging railroad. Despite the slow business, P&S extended the logging railroad from the Agua Fria Valley up Rivera Canyon into Valle Largo. The road crossed the Oso Ridge and the Continental Divide along the crest. By 1939, the line had been extended another eight or nine miles to the point beyond the little village of Tinaja south of the Oso Ridge. Logging camps were established at Valle Largo and near Tinaja.

In the typical manner of rail operators, P&S acquired more equipment. Eight boxcars were used for supplies and storage. P&S also installed a new diesel power plant in the old American log loader, which was originally steam-powered. Another large locomotive was leased from the ATSF and was ultimately purchased. This was Number 678, a good-sized 2-8-0 type similar to the earlier Number 648.

The railroad in Valle Largo faced a challenge due to the steep four percent grade that went eastward and worked against loaded log trains. As a result, the capacity of the railroad was severely limited. The two former AT&SF rod locomotives could only pull four loaded log cars uphill, while the bigger Shay could handle seven or eight. Using these heavy locomotives required a solid roadbed, which is why the Valle Largo railroad through Rivera Canyon was substantially constructed.

Prestridge and Seligman ceased logging out of Grants in 1941 and sold their equipment to GEBLbr Company. The inventory of equipment included the following:

- 1 Shay locomotive

- 1 Rod locomotive, #648

- 1 Rod locomotive, #678

- 5 Boxcars at Camp

- 2 Boxcars at Tinaja

- 1 Boxcar at Grants

- 16 Cabins at Tinaja

- 1 Cabin shop at bonding

- Approximately 10 Skidding Rigs

- Approximately 10 Sets of Harness

- 1 Diesel power unit, installed in American Log Loader, which is the property of George E. Breece Lumber Company

- 21 Horses

- 2 Mules

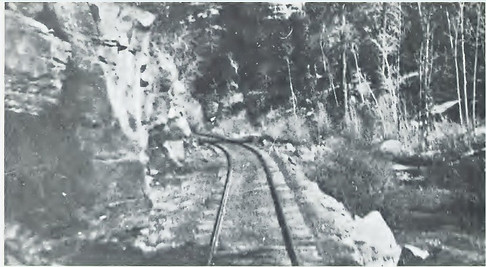

The railroad into Valle Largo in the southern Zuni Mountains is a study in contrasts within its length and other logging railroads in the district. The portion of the railroad examined in detail extends across Sections 25, 26, 27, and 36 of T. 10 N, R. 13 W. At the head of Rivero Canyon, the line curved across a deep ravine on a solid earth fill approximately 20 feet in depth and over 100 feet in length. The fill has remained intact except for the subsidence caused by the collapse of a wooden culvert at the fill's deepest point. The line entered a rock cut, four to five feet deep westward from the fill. Beyond the cut, the roadbed ran on the ground with a minimum of grading until it dropped into an extended, steep rock cut leading down into Valle Largo.

The roadbed is littered with numerous rotting crossties, many with track spikes still driven into them. Impressions of rail left on many ties indicate that the track was laid with 60-pound-per-yard rail directly on the pine ties without the benefit of tie plates.

The cut carrying the track into Valle Largo involved considerable effort in its construction. Nearly a mile in length, the cut ranges from eight to 15 feet deep in mixed rock and earth. The gradient was almost four percent for the entire cut length. The steep grade, which was against the loaded trams of logs, explains the use of heavy mainline locomotives by Prestridge and Seligman in contrast to the much lighter locomotives used elsewhere in the district.

Beyond the long cut, Valle Largo opens into a broad tree-rimmed valley about a mile long. The railroad bed all but disappears as it crosses the open space. Only a few rotting ties mark its route today. In the valley are the remains of a logging camp with two surviving log buildings, a cold deck for storing and loading logs, and signs of a single rail siding.

The logging camp had two main log buildings which acted as its center. It is possible that the camp also included several portable cabins and railroad car accommodations during the peak of its operation, as stated by Prestridge and Seligman in 1941. The larger of the two log buildings was 34 feet wide and 134-1/2 feet long, but its purpose could not be determined through a quick examination. On the other hand, the second log building was approximately 20 feet square, and the presence of piles of ashes and slag inside indicated that it was used as a blacksmith shop.

The railway line extended westward from Valle Largo, following a stream bed. The roadbed was constructed by using local rock, thus forming a ledge on the north bank of the predominantly dry stream bed. Upon reaching Section 26, T. 10 N., R. 12 W., the railroad continued along the valley until it opened out near Tinaja. The railway's termination point was located a short distance north of the village.

It is surprising that a sturdy and durable roadbed was constructed for a logging spur that had a limited lifespan. However, the construction could be justified to some extent by the four percent grade that the loaded log trains had to overcome when departing from Valle Largo. Heavy locomotives were required to pull viable trains, which in turn necessitated a solid roadbed. While it could be argued that lighter locomotives making additional trips up the short climb would have been equally effective, the use of heavy-duty engines was a pragmatic choice.

It is plausible that the railway line was intended to be a heavy-duty main line to access the timber on the entire southern side of the mountains or perhaps the initial phase of a lengthy mainline, as described in Appendix C.

Limited records document the activities of the George E. Breece Lumber Company (GEBLbr) after it shifted to truck hauling for timber cut outside the Zuni Mountains in 1938. When Prestridge and Seligman divested their interests, Breece no longer required the Grants railroad. Efforts were made to sell the locomotives that idled at Grants, but the attempts proved futile. The Saginaw and Monistee Lumber Company in Flagstaff acquired the 130-ton Shay locomotive, while the remaining assets were sold for scrap.

Throughout 1941 and 1942, the George E. Breece Lumber Company ceased its operations. In May 1941, the Alamogordo sawmill and the Mescalero Apache timber rights were sold to Prestridge and Seligman. The Albuquerque sawmill continued to operate, but the company faced a strike by employees over wages in May. The strike persisted for an extended period, exacerbating the company's problems. Despite logging and sowing timber through the summer of 1941, the company liquidated the property by 1942, marking the end of the George E. Breece Lumber Company.

To read more about the following click button below:

The Mcgaffey Co.

luther & Moore Lumber Co.

Zuni Mountain Railway route map, as laid out and surveyed by S.M. Rowe.

Circa 1903-1904 Albuquerque Lumber Company: Sawmill, sawdust burner, and lumber storage yard. Albuquerque, Bernalillo County, New Mexico Territory. V.J. Glover collection

1908 - Plans for the Albuquerque Lumber Company. Albuquerque, Bernalillo County, New Mexico Territory *with the City Electric light plant.

1908 - Locomotive Number 4 was purchased by the Zuni Mountain Railway in 1903 and used since then for years in the mountains for track maintenance. Photo taken during the winter at Kettner. John Bigley Collection

1908 - Map showing the junction from the SFP mainline from Thoreau (formerly Mitchell), and the American Lumber Company built to the south from there. Work began in 1903 to the standard gauge Logging railroad and operated under the Zuni Mountain Railway name. This line allowed for shipments of logs from the Zuni Mountain area to Albuquerque from the SFP mainline. As seen above Kettner and Paxton Springs is in the irregular outline that is the approximate boundary set by the current administration of the USDA-Forest Service (Cibola National Forest),

The wooden Zuni Mountain Railway cars are loaded with logs using one of the American Lumber Company's steam loaders which sits on skids and has a stiff-leg boom attached loading logs to the car. The chains seen are securing the first two layers of logs then two or three more logs are added on top then secured before hauling. Cibola National Forest Collection

1912 - Santa Fe Railways locomotive Number 826 is seen hauling logs through Laguna, New Mexico. During this time the train has a mix of steel log cars from the Santa Fe Railway as well as the wooden log cars of the Zuni Mountain Railway usually seen at the back of the train. John B. Moore, Jr., Collection

View of Kettner's main logging camp, with workshops and plenty of maintenance facilities. This area was devoted to all railroad and mechanical matters. Cibola National Forest Collection

Zuni Mountain Railway Locomotive Number 6, now obsolete was purchased from a Chicago dealer and worked it till its last years. Number 6 seen here is leaving Kettner and headed to Thoreau, New Mexico

Zuni Mountain Railway's Climax Locomotive Number 8 brings two carloads of logs to camp. Cibola National Forest Collection

Zuni Mountain Railway's 133-ton 2-8-0 locomotive No. 12. John P. Bigley collection.

Zuni Mountain Railway's log cars, waiting to be switched to the sawmill, are seen at the Santa Fe Railway depot in Albuquerque. On the left, the Albuquerque passenger depot and Alvarado Hotel can be spotted. V. J. Glover collection.

The loading of standard 16-foot logs on the Santa Fe Railway steel log cars is done using this steam loader equipped with a rigid boom, end slides from car to car on skids. Cibola National Forest Collection

Zuni Mountain logging Spur. John Bigley Collection

This picture is of the Zuni Mountain Railway mainline that runs through Cottonwood Canyon. The picture shows the strong construction methods used to build permanent railroads. Jim Bigley Collection

The American Lumber Company uses big wheels to skid logs to the railroad. Cibola National Forest Collection.

The American Lumber Company has landed logs along a future spur track in a small valley, with the intention of loading them onto cars once the spur track is constructed. The roadbed has already been graded, indicating that preparations are underway for the development of the track. Cibola National Forest Collection.

Zuni Mountain Railway locomotive Number 4 was used for track-laying during a big logging project. It was quite a challenge to coordinate logging and railroad construction to efficiently cut trees and use the limited available rail length. In many instances, the logging was done before the rails were laid. This view appears to show one such instance. Cibola National Forest Collection

This view showcases some intriguing logging practices. A "bummer," a low-wheeled truck, was being used to skid a large log. The truck's small wheels necessitated flat and moderately firm ground for its operation. The railroad had a spur laid with aspen ties, an unusual timber choice for this purpose. The presence of spikes driven close to the sides of the ties indicates that the ties were intended to be used at least once more on another spur line, with spikes being driven on the opposite sides for the second use. Cibola National Forest Collection.

A team of two horses, each harnessed to a wagon bearing a sizable load of logs, poised to be deposited at a railroad landing. In the background, an industrious worker from the American Lumber Company stands alongside a string of cars, ready to begin the day's labor. This scene captures the essence of the harmonious collaboration between nature and humanity, as evidenced by the efficient endeavor to transport the logs to their final destination.

.Zuni Mountain Railway Shay Locomotive No. 3 bringing a train from the woods. John Bigley Collection

Located in Sawyer and owned by the American Lumber Company, the logging camp provides a glimpse of the typical construction of logging railroads in the region. The railroad track construction is characterized by a minimum of grading, the use of steep grades, and earth ballast between the ties. The switch in the image is an excellent example of this type of construction. The switch ties, which range between eight and sixteen feet in length, serve as a testament of the railroad's former presence, long after the tracks have been removed. Cibolo National Forest Collection